Before You Start

Listen to the Original Broadway Cast Recording

Mandy Patinkin and Bernadette Peters are such distinctive and unusual performers that every subsequent performer has to find a way forward that doesn’t imitate them. But the show is built around them, and their shadows loom very large over the show itself. The mix on the recording is odd. Some singers seem far away, and instrumental timbres are often unclear. But it’s still an amazing document.

Listen to the 2017 Jake Gyllenhall/Annaleigh Ashford recording

This is a really fine record of Sunday in the Park with George. The orchestra in particular is very well recorded, and there are a number of things that can be heard clearly here that are somewhat obscure in the original recording. I was initially skeptical about Gyllenhall’s casting, but I’m sold. Annaleigh Ashford is quite good, although these old fashioned ears sometimes wonder about vocal choices here and there.

Listen to the 2006 London cast recording

I believe this is the production that had some truly extraordinary projections that I suspect consumed a lot of the production budget and necessitated the drastically reduced and revised orchestrations. These sometimes are rather thin, and are after all, not the ones you rent when you license the show. Hearing the opening horn line on a saxophone is somewhat jarring. The first act uses UK dialects, which are often revelatory. After all, as long as we’re singing in English, even though we’re in Paris, why not explore other dialects? To my American ears, the dialects in Act II are far less convincing. This recording is a terrific way to explore new ways of singing these songs.

Watch the video of the original production

Someone has helpfully put the whole production on YouTube, but I own a copy on DVD, and you might want to as well. There are a number of places in the show where something seems confusing in the score. The video very helpful shows how the music was originally integrated into the action. You will want to find your own way of navigating the show for your particular production, so it will be prudent to go to the video when you need clarification.

You might treat yourself to a kind of hybrid experience by watching this delightful video.

Read James Lapine’s incredible book Putting it Together: How Stephen Sondheim and I Created Sunday In The Park With George. It’s a detailed and very candid behind-the-scenes look at the making of the musical, in which Lapine doesn’t shy away from unflattering details about himself. If you know Sunday well, you’ll be amazed by revealing stories about how the musical came to be, and if you don’t know Sunday… Well, you will by the time you finish the book.

Should Your Organization Do this Show?

All Sondheim shows are extremely challenging. This one is difficult for the tech crew, but there are ways to creatively overcome the difficulties. You must have a George and a Dot; the other roles can be filled from a general pool of musically proficient actors. There are very challenging pit parts that may do in amateur musicians.

As You’re Casting:

Georges/George

You will need to cast a very strong tenor with a good ear in this role, an excellent musician who holds the stage with ease and can handle the pressure of holding down a very technically complicated show. The role doesn’t have a lot of high notes, but it lies high for a baritone. First act Georges does a lot of unsympathetic things, so you will need a really likable actor. Putting It Together and the Fifi-Spot section are must-sings in callbacks. Perhaps some of Color and Light would be helpful too.

Dot/Marie

The role of Dot is one of the great roles for women in the American Musical Theatre. She has a really difficult arc and a lot of difficult music to manage. (although I think the role is easier on the whole than George’s) In callbacks, you’ll want to hear some part of Move On that shows the ability to count, and some of Everybody Loves Louis. Sondheim used to joke that he envisioned George being a baritone and Dot a soprano and in the end they cast a baritone as Dot and a soprano as George. That’s an exaggeration, of course, but it’s good to have a somewhat earthy Dot.

Old Lady/Blair Daniels

The traditional casting of the same actor in both these roles is fun and interesting, but not mandatory. The song at the end of the first act is very difficult both to hear and to sing in time, and it’s dramatically very important. This is a role for a good musician and experienced performer. In the right hands this number grounds the first act narrative in a really critical way. Casting a really fine actor in this role makes George’s journey more believable and gives him something strong to play.

Jules/Bob Greenberg

This is not a particularly vocally challenging role, (the higher notes are not sustained in the phrase) but you do need a good ear, and this actor needs some gravitas. The Jules/Greenberg pairing is dramaturgically very interesting, but you could cast it in a different pairing if you so chose.

Yvonne/Naomi Eisen

This traditional pairing of Act I and II roles doesn’t have any deep hidden meaning as far as I can make out. The scene between Dot and Yvonne is subtle and important. Like Jules, this requires a good ear. You will want to hear “It might be in some dreary socialistic periodical”. from No Life in callbacks.

Soldier/Alex

This is a wonderful small comic role for a strong baritone or tenor. I was bewildered that quintessential baritone Robert Westenberg covered Mandy in the original production until we cast a wonderful tenor in the role for our production and I began to see the connection. The pairing of first and second act characters is a fruitful one in terms of themes, but you could pair it a different way if you needed to.

Boatman/Charles Redmond

The Boatman stands in the outsider role that was so important to Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musicals. He tells the truth nobody else wants to hear. The vocal part has some difficult timing. You will want to hear the “You and me pal” passage in The Day Off at callbacks. The pairing with Redmond isn’t very meaningful, and Redmond’s part isn’t any more or less difficult than any of the others in Art Isn’t Easy, so you could cast the doubling differently if you wanted.

Nurse/Mrs./Harriet Pawling

The nurse only has one brief singing passage, but it’s somewhat tricky, so you’ll want to hear it in callbacks. Ideally has some chemistry with Franz and is a sufficient foil for the Old Lady. This role is often double cast with Mrs. She doesn’t sing as Mrs., so you can cast to the funniest actor for the part. The role of Harriet in Act 2 doesn’t particularly resonate with Mrs., but she does interact with Marie, the ‘Old Lady’ of Act II, so you might want to keep the traditional doubling. Harriet sings higher than Nurse, at least as high as F, but even higher if you don’t alter her part in 29 P.

Mr./Lee Randolph

Not singing roles, so you should cast the funniest actor for Mr.’s scenes. The pairing is not necessary, except perhaps that Mr. and Lee are both involved in arts patronage.

Franz/Dennis

Franz needs a decent German dialect and chemistry with the nurse. The pairing with Dennis is not necessary. Dennis doesn’t really sing in act 2, but he has a very important scene with George. If you do cast the same actor for Franz and Dennis, it’s a chance for a strong actor to play some very broad comedy and a rather touching realistic scene in the same show.

Frieda/Betty

Frieda also needs a German accent and chemistry with Jules, although this chemistry can be unusual, since their relationship is clearly made much more exciting through transgression. Betty sings very little in Act II.

Celestes 1 and 2/Waitress, Elaine

The two Celestes are essentially interchangeable. Ideally you have two very similar actresses who have good comic chemistry with each other and with the soldier. The Act II parts are both quite small. The waitress doesn’t speak. Elaine has 7 lines. (in a nice scene)

Louis/Billy Webster

Louis barely speaks; he’s almost an idea. Unless I’m missing something, the range I’ve included above is from his one singing line at the top of Act II. If you double cast with Billy, the range is wider, essentially the same as all the other singers in Putting it Together.

Louise

The trick to casting this is to get someone old enough to be reliable in It’s Hot Up Here, who is nevertheless young (or short) enough to read the right age for this part. Consequently, this is a role you may want to delay casting in a professional production. 6 months can make a big difference in height for young people the age you will likely be looking at.

A Few Things to Note About the Music Director’s Materials

The original published score is very well laid out, as are all the Sondheim scores of this time period. I was nervous about the re-engraved piano vocal score that come with the rental materials, having played from the new engraving of the Into The Woods score, which is not an improvement on the original published score. This new Sunday is very good, easy to play from, and well cued to the orchestra parts. If you compare the two piano vocal scores, though, you will see hundreds of minor discrepancies, and a couple significant errors, which I’ll note below.

The vocal/script books and orchestra books are also very good, with only a few minor errors I will also note.

Going Through the Show Number By Number

I’m not the first person to note that the acts have a number of matching pairs.

| ACT I | ACT II |

| Sunday in the Park With George | It’s Hot Up Here |

| Color and Light/Gossip Sequence/Finishing the Hat | Putting it Together |

| Color and Light | Chromolume #7 |

| Finishing the Hat | Lesson #8 |

| We Do Not Belong Together | Move On |

| Beautiful | Children and Art |

| Sunday | Sunday |

This parallel construction obviously brings an internal coherence to the piece, made stronger still by musical material appearing in multiple songs, developing the ideas and characters in subtle transformations. But the parallels also highlight the differences between the acts. The painting sequences in Act I show how a disconnected George is bringing a vivid world of characters to the canvas. When we reach the parallel sequence in act 2, we find George talking to everyone. He’s the product now, not the painting. Finishing the Hat and Lesson Number 8 are both about artists’ problems, but they reveal two totally divergent states of mind. First act George is in a flow state. Second act George is blocked.

In any well made musical, a reprise helps us make sense of time passing, themes developing, and ideas changing. Apart from the finales, these are not reprises at all. They are echoes of situations and people in time. Stephen Banfield makes a lovely point about these parallels, noting that Sondheim and Lapine had originally meant to be a show made up of a theme and variations.

“The whole artistic question of when to repeat and when to do something different… is what George’s crisis in act 2 is about.”

We see in the macro the ideas explored in the micro. This is a hallmark of many masterpieces, and a calling card for Sondheim in particular.

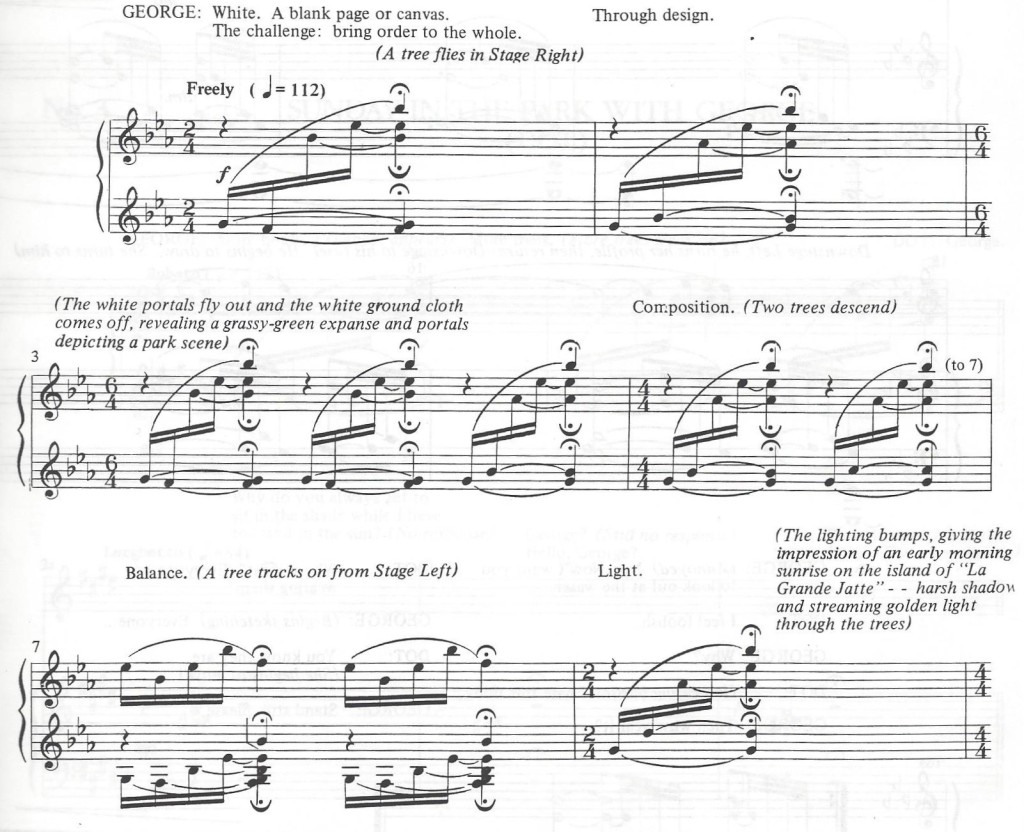

- Opening-Prelude

This fanfare has always read to me as a kind of idealized perfection of creation; the world as George wishes it. We will descend almost immediately into a state of imperfection, but this first gesture establishes George’s kingship over the world he is trying to create. This fanfare will undergo a number of important transformations, morphing into the horn fanfare in The Day Off, the melodic idea of both Finishing the Hat and Putting it Together and the underscore of We Do Not Belong Together and Move On.

Right away there is more information in the old piano vocal score than we have in the new materials. The original score includes some instructions on the chords themselves for when things fly in. These are not terribly significant in the long run, though, because the tech for these elements will likely determine the timing. We performed this in a proscenium theater with a fly space, but flying in giant trees or pulling white drops back from tree legs is an all-hands-on-deck situation. You may discover you need to take quite a bit of time on each fanfare fermata.

Measure 9 contains one of the most difficult passages for horn in the musical theatre repertory (more information on that when we come to talk about pit players)The part is extremely high and very exposed. The player will need to play it at a decent volume to get the note secure and in tune, but horns tend to sound a little thin up there, so the quiet dynamics in the other players will be very unlikely to be drowned out by the horn line.

- Flying Trees

This is, on the face of it, a clever theatrical joke, throwing us as an audience a curveball and letting us know that we are not watching a strictly realistic world. But it’s also a key to a major theme of the piece.

It was one thing to open the show with an artist bringing a world to life. But that world, populated by presumably real people, is also being continually edited by the artist, and we watch it being edited. The Old Lady can see that the tree is missing. Are we in George’s mind or not? Is the Old Lady the only person who can see what George is editing? Their connection becomes more important as the act progresses, because the Old Lady is the catalyst that moves George from the devastation of We Do Not Belong Together to the triumph of the first act Finale.

If you made it through the opening, you’ll be fine here musically.

- Sunday in the Park with George

Sondheim includes the monologue Lapine wrote at his request which became this number in his book Look, I Made a Hat. It’s well worth looking at this monologue, and reading his commentary about it. He would organize the number around her short attention span and her physical discomfort.

This number has become so iconic and familiar by now that we may have to work to remember how unusual it is. It is almost as shocking as the beginning of Oklahoma would have been compared to normal expectations of a musical’s opening number. There is no chorus, the few characters on stage have shared an odd, mannered, rather low-key scene before the number proper. The percussive and spare accompaniment is packed with minor seconds, expressive of Dot’s discomfort, and her brief bursts of melody require our full attention to understand the form. In a costuming tour-de-force that is also totally grounded in the narrative, Dot unexpectedly steps out of her dress. The music begins gradually to leave ‘my-foot-is-falling-asleep’ angularity and creep toward something more ardent, and Dot introduces important themes: she is the first to say the word ‘connection’ and the first to raise the idea of permanency. Permanent expression. Durable. Forever. When Dot finally does break into full lyricism, we are given what will become the musical’s most rhapsodic and structurally important material, first:

“Your Eyes, George”

And then

“Most of all…”

In these critical moments, we discover why Dot remains there: George and his painting are beautiful.

As Dot steps back into her dress, we are thrown once again into claustrophobic paresthesia, and we experience her discomfort viscerally ourselves. It is a microcosm of the journey of the show from the beginning through the top of act II.

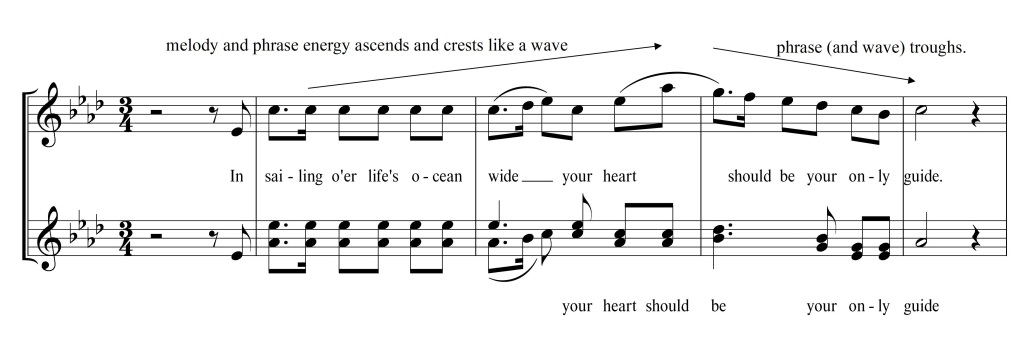

If you read part one of this blog post, you will recall my saying Sondheim is a minimalist composer. One of the ways he uses repetition is to build phrases from small cells of notes. When his characters become stuck in a loop of pitches, they have invariably also gotten caught in a loop of thought, as Dot does here, when she sings:

“There are worse things than staring at the water on a…”

And then, of course,

”There are worse things than staring at the water as you’re posing for a picture after sleeping on the ferry after getting up at seven to come over to an island in the middle of a river half an hour from the city…”

The melodic repetition makes us feel trapped with her in rumination, and the release is a kind of minor catharsis. Consider similar passages and you’ll begin to notice them all over Sondheim:

Another hundred people just got off of the train…

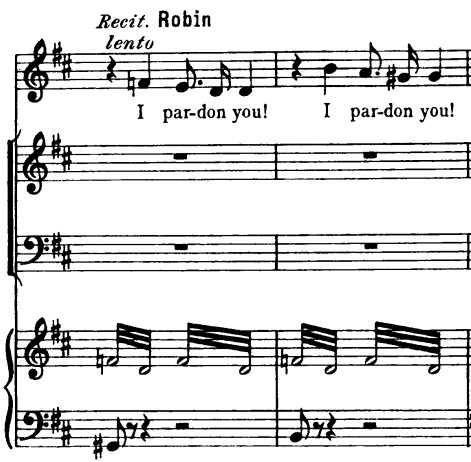

Pardon me, is everybody here, because if everybody’s here…

What if he knew who you were when you know that you’re not what he thinks that he wants?

Throughout the number, George does not sing, but instead intrudes on her thoughts with unwelcome corrections. Every expression of her physical self is rejected.

“Don’t move, please”

“Eyes, open, please.”

“Look out at the water, not at me.”

“Don’t lift the arm, please.”

“The bustle high, please”

“Don’t move the mouth.”

He is not, in fact, trying to get to the bottom of who Dot is. He is trying to make her appear the way he wants her to be. The number establishes immediately that our place is with Dot, trying to figure out George, and trying to find a place in his world.

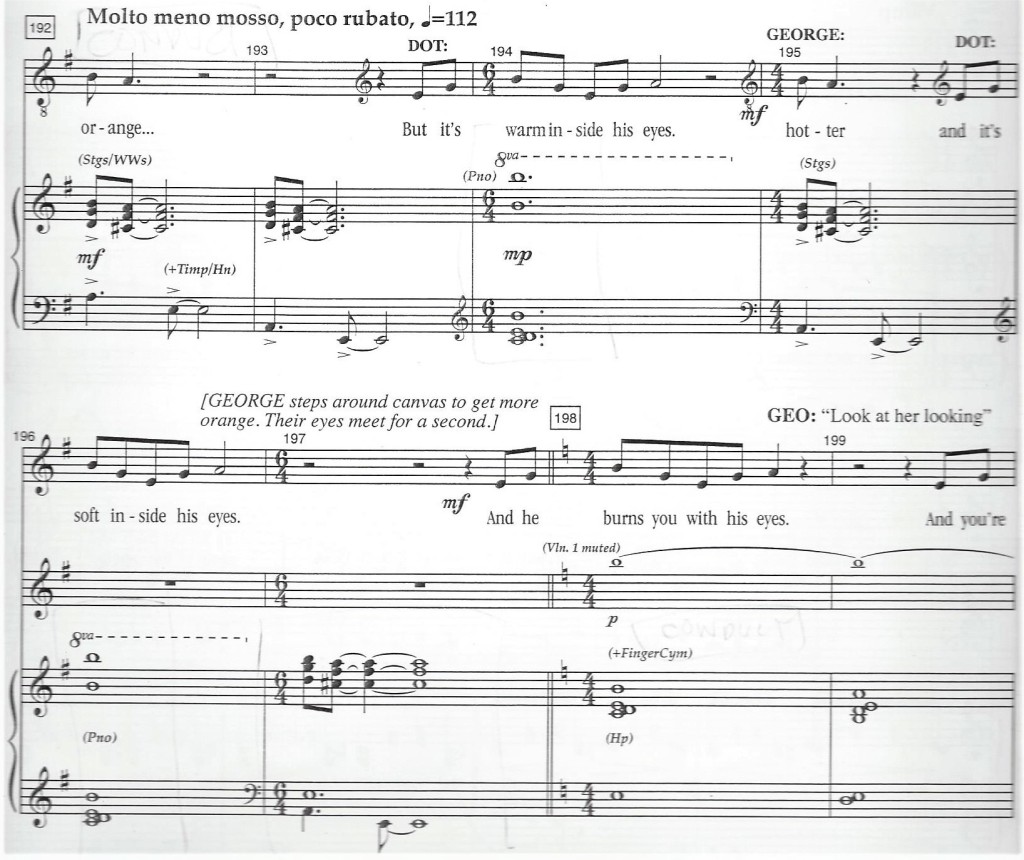

The pensive chords that accompany ‘Your Eyes, George’ melody are a motive that runs throughout the show. If you track the appearances of these ruminating chords sequentially in the show, you can see in brief the whole trajectory of their relationship, even through to Act II:

“Your Eyes, George…”

“If my legs were longer”

“If I was a folly girl…”

“And he burns you with his eyes”

“If the head was smaller…”

“Hello, George, where did you go, George?”

“The bread, George…”

“We lose things, and then we choose things”

“Yes, she looks for me. Good.”

“Yes, George, run to your work…”

“What I feel? You know exactly how I feel.”

“Hello, George, I do not wish to be remembered like this, George”

“Alright, George. As long as it’s your night, George.”

“Say Cheese, George, and put them at their ease, George”

“Be New, George. They tell you till they’re blue, George.”

“Elaine, fix my chair so I can see Mama…”

“Charles has a book, Charles shows them his crayons…”

The more active pattern of sixteenths that follows, as Dot sings “But most, George, of all, but most of all.” is another motivic accompaniment pattern that we will hear less frequently through Act I. Tracking those:

“But most of all, I love your painting.”

[Scene Change from Old Lady into Studio]

“Well, Louis, and George, but George has George”

“But if Anybody could… Finishing the hat…”

When the motive appears in Finishing the Hat, it has been slightly altered, becoming an accompanimental grounding for George’s most important cri de coeur. More on that later. This set of musical ideas in the first complete song in the score strongly establishes the sound world of the musical. Now to more prosaic matters:

The original score here marks the first measure Rubato, (quarter = 112 bpm)

Measure 2A is marked Larghetto (quarter = 84)

Measure 6 has a lyric error. (now THE foot is dead)

The triplet rhythm in vocal in measure 7 is not in the original score, and seems out of left field to me.

Measure 9 is originally marked poco mosso (quarter = 82)

Measure 18 is originally marked Strict tempo (quarter =92)

Measures 34 and 35 are tricky. If you play it in your left, it’s somewhat awkward to get under your fingers, particularly over and over again. If you break it up between left and right, you may find it more grateful. I’m sorry to report that the orchestration doesn’t really help you. The figure in the left is split between the viola, the cello, and the double bass, and the timbre differences between the instruments keeps the figure from cohering really. The melody doesn’t ‘pass off’ from one instrument to another. I added the viola notes to the cello, which seemed to give it body. It’s a neat figure, and it covers some business, so the audience has little to do but listen! It’s also an awkward loop to escape, since when you leave the vamp, it sounds like the same measure until the end. I explained that my signal would take us out of measure 35, not out of measure 34. You will have to formulate your own solution to this little nub.

Measure 87 should be in 4. (quarter = 92) in the original score. You will have this figure a lot in the show. Sometimes it’s in 2, sometimes in 4.

There is an error in the bass book in the last note of measure 107. That should be a G, not an F.

- Parasol

You’ll have to find out from your director what this fanfare actually illustrates. In our production it coincided with a parasol opening. (which is not the cue in the score)

- Yoo-Hoo

This is slower than you might imagine for musical ideas like this. It was originally a longer number, and was cut down on its way to Broadway. You can see the original lyric in the published libretto and in Look I Made a Hat.

- No Life

We again see George through the lens of others. As usual, Sondheim is accomplishing many things: establishing the convention that we will see paintings appear from the world of the piece, establishing the values of the art world George is defying, establishing Yvonne’s attempts to be witty enough to please Jules, all over a stately promenade, to which the harpsichord lends a musty pall.

In Sondheim’s notes, we see he was originally planning a series of promenades to connect the vignettes, an idea inseparable from Mussorgsky’s 1874 Pictures at an Exhibition, in which a recurring promenade leads us through an imaginary gallery, and each ‘painting’ is a characteristic piano piece. No Life serves such a purpose here, although Sondheim’s original intention to connect Act I using this device doesn’t go much further than this.

This is one of the places where Sondheim is also clearly referencing French impressionism. (it’s a Satie Gymnopédie) It is very easy to overpower the dialogue and vocals here, lower the written dynamic after the repeat section by at least 2 levels. The English Horn in particular can be somewhat aggressive in that register.

The passage beginning at measure 58 is not in the original piano vocal score, but it was in the original production. It also tends to overwhelm the dialogue, and can easily be cut or truncated.

- Scene Change to Studio

This is just a truly lovely scene change, particularly with the harp and celesta sounds. If your scene change is running long, you may well want to repeat the first 8 bars so as not to park on D minor for too long.

- Color and Light (Parts I-IV)

“If there is any song in the score that exemplifies the change in my writing when I began my collaboration with James Lapine, it would be ‘Color and Light’… I organized this song, and much of the score, more through rhythm and language than rhyme.” -Sondheim

Sondheim truly breaks new ground in musical theatre here. It might even be argued that he himself never again surpassed this sequence, and certainly none of his imitators have either.

We have thus far only seen George as reflected through the lens of those around him. We haven’t heard him sing yet. But now we see and hear George for the first time from, as it were, his own perspective. We catch the excitement of flow, and we see him address his artistic subjects like a director or a dictator, even in their absence, editing their essences.. “So black to you, perhaps. So red to me” The subject of the painting has no agency in the portrayal.

We also see Dot editing herself, her powderpuff in counterpoint with George’s brush strokes. She is trying to discover a version of her identity that bears significance, and one that bears significance to George. We come to see that George’s eye is his power not only to paint, but his power over Dot. The counterpoint between the two escalates until the climax, “I could look at him/her forever” The moment is made somehow more poignant by the clarity that these two are so deeply alienated from one another even in their most unified moment. The grounding musical motive that underpins this thrilling ending is a development of the Red-Red-Orange theme.

This accompaniment pattern only appears three times in the show, but they are the most loaded expressions of attraction and alienation between the two of them.

“You look inside the eyes and you catch him here and there, but he’s never really there…”

“Let her look for me to tell my why she left me, as I always knew she would”

“What you care for is yourself. I am something you can use.”

The fact that the motive is built from the musical motive associated with George’s flow state makes the point quite beautifully. George’s artistic lifeblood is also the source of his alienation.

“I care a lot about art and the artist. The Major thing I wanted to do in the show was to enable anyone who is not an artist to understand what hard work it is.”, Sondheim told Craig Zadan. Color and Light is where that hard work is most clearly depicted.

Compare this detailed depiction of artistic process and personal alienation to The Last Five Years for example, where we hear Jamie crow about the results of his success, and we even see him spinning a yarn in the Schmuel song, but we don’t get any sense of what his artistic process means to him. We also have no clear idea of what Cathy thinks of his work and her connection to it. This is one of the reasons most audiences don’t think Jamie is the protagonist of L5Y. It’s a choice between his relationship and his ego, not his art.

Here we are thrown deeply into the creative process itself, made even more vivid by the lack of traditional song or lyric structure. When Dot sings about the Follies, we flirt with a traditional song form, but the passage reads as a stream of consciousness. It’s a testament to Sondheim’s mastery of musical rhetoric that the piece doesn’t fall apart at the seams or overstay its welcome. It helps that Sondheim had written something of a conceptual rough draft in Opening Doors in Merrily, where Franklin Shepard is editing and editing the tune he’s writing as the world spins around him. It also helps that George isn’t writing music. The worst scenes in musical biopics are usually the ones where the composer is tearing his hair out at the piano trying to arrive at the tune the audience already knows by heart. But here we are not imagining the destination of what George is painting so much as sharing in his excitement of the work itself. We can’t even see what he’s painting, so our imagination has to take over.

Sondheim establishes a technique here that stakes out a major theme of the work: I like to think of it as Windows. He will use the idea again in Into The Woods to establish the options in points of decision. Into The Woods is about the unintended consequences of decisions. Sunday is in some sense about the distinction between the reality of being a human and an artist’s depiction of that reality. The musical geography is critical to Sondheim’s portrayal of that theme

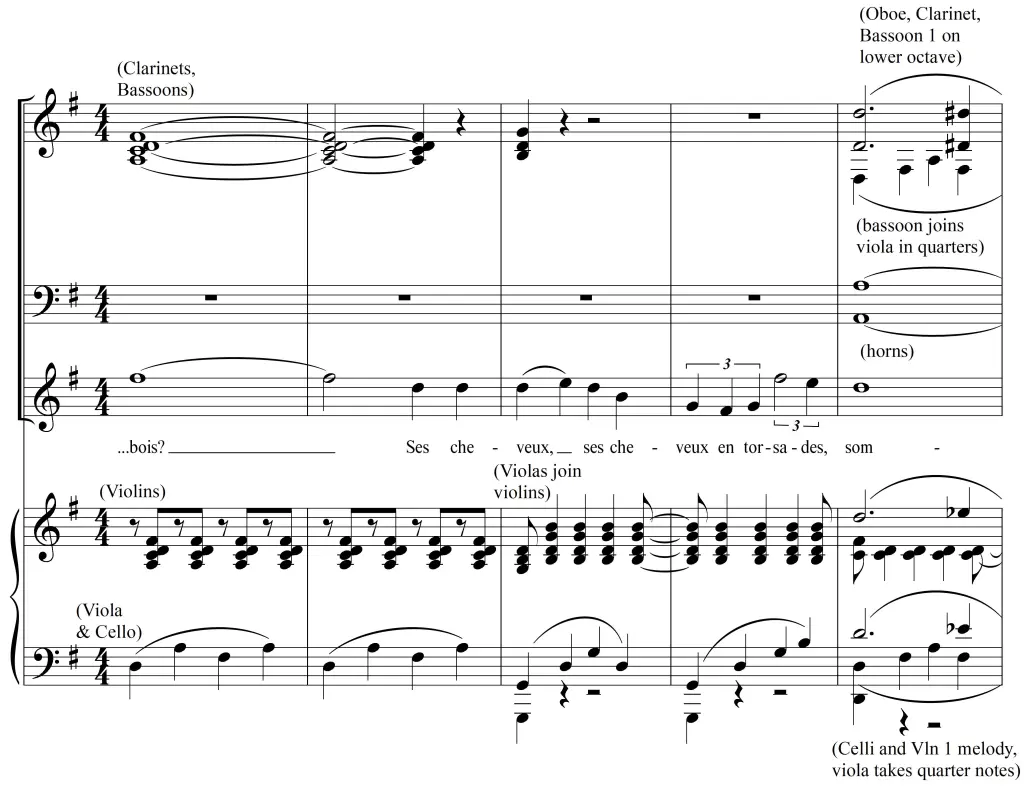

Notice that George’s ideas have a lower accompaniment, Dot’s accompaniments are much higher. (this is harder to make out in the original piano vocal score layout) We ultimately hear Dot’s accompaniment becoming the pensive two chord idea she introduced in the opening.

“Your eyes, George”

These two musical locations, one low, and the other high, are placed in close proximity to one another so that we can experience the gulf between them. This back-and-forth is broken by the stage direction:

[George steps around canvas to get more orange. Their eyes meet for a second]

In other words the dual world musical dichotomy is broken by an actual person-to-person connection, made just as the music shifts to the accompaniment they share troughout the musical.

We will see later in the piece that this delineation of musical real-estate is a critical area of exploration. How much of what we are seeing is real and how much is George’s construction? It all has to do with these windows. (more on that later)

If you’ve hired keyboard 2 (and I sure hope you have!) You will want to go through keyboard 1 and mark what you’re playing and what you’re conducting. It’s a great challenge to switch back and forth, and cue the singer where necessary. Getting into measure 92 in part 3 can be tricky; you will need to run it a few times to get the tempo to drop in correctly. The passage beginning in measure 112 is hard without a bass player, because neither hand is intuitive really. Take some time to work through measure 144, especially if you are conducting from the piano. If you know what you’re doing, it works well. If not, it will be a struggle. The top note in the right hand in measure 156 should be F natural. The timing in measures 200-204A can be tricky to line up with the vocals. You may have to move rather quickly through the whole notes and potentially cut the repeat of 205. The existence of 205A and 205B indicates this was an issue in the original production as well. The end of 8B is a really neat effect, rather like the subito piano at the end of Epiphany from Sweeney Todd. It is also somewhat unsatisfying because Dot leaves without a button and nobody can applaud her in what is one of her more beautiful moments. The very last measure of 8C is tricky to land. After goofing it more than once, I actually dropped out in measure 250, conducted, and played beat 2 of the last measure. There’s plenty of tutti there, and a clear button is essential.

- Scene Change to Park

This cue is almost all music we’ve heard before. The entrances of the Boatman and the Celestes are ideally cued to the phrases that begin on measure 11.

- Gossip Sequence

Having heard from Dot and from George himself, we are again amid the other subjects of the painting. Sondheim introduces ideas we will encounter later: The Celestes’ “They say that George has another Woman” will become:

“I mean, I don’t understand completely”

“It’s not enough knowing good from rotten”

Etc.

The Old Lady and the Boatman show a certain misanthropic musical kinship here, although the Boatman accompaniment is 3 octaves lower with a more dissonant minimalist polyrhythm (see earlier post)

Our appreciation of the larger meanings in the work will be deeper if we catch some subtle distinctions here:

The Celestes, the Nurse, and the Old Lady are trying to keep up with the romantic news; Dot has left George, George behaves unusually. They are uninterested in his work. “They have so little to speak of, they must speak of me?”, George asks at the top of the show, and he’s right.

The Old Lady is pragmatic. You can’t make enough money to raise a family by painting. She also brutally assesses people with a single word: Noisy. Famous. Filthy. Deluded. Unfeeling.

Jules and Yvonne are concerned with the oddity of George’s new technique and complaining about what George is painting. Boatmen and Monkeys are both inappropriate subjects.

The Boatman cuts through to deeper truths. He relishes his status as an outsider. The companionship he most enjoys is the friendship of the dog, primarily because the dog does not make demands and allows the boatman to be who he is, unexamined. To the boatman, the Celestes, The Nurse, the Old Lady, Yvonne, Jules, and George have all fallen into the same foolishness: trying to observe things. After all, what are these drawings even for?

The characters are so interesting and funny that we may miss a larger point: All of them are making judgments and assuming intent constantly, especially the boatman. Only George is permanizing the judgements.

An interesting musical coincidence may be noted to Sweeney Todd:

These similarities in melodic contour are unintentional, of course, but they are examples of the coherence of Sondheim’s mature style, in which these odd melodic shapes are organized and re-organized to fit the same stream of consciousness the character is navigating.

The accompaniment is a little math game, and a tricky one at that. You’ll notice the right hand is playing a 4 note pattern. The left gives us a dissonant 2 notes, then 3, then the pattern repeats and gains momentum. By measure 6, the two hands settle on a 4 note pattern for 2 measures, but then the left becomes a pattern of 3 notes, against continuing four note patterns in the right.

Measure 19 is so interesting, you will be tempted to play it loud, but mark everything piano, because you’re playing under some dialogue here, and the scoring is heavy. If you’ve managed the earlier 4 against 3, then the passage beginning in measure 38 should start well. But then the pattern in the right starts to change…

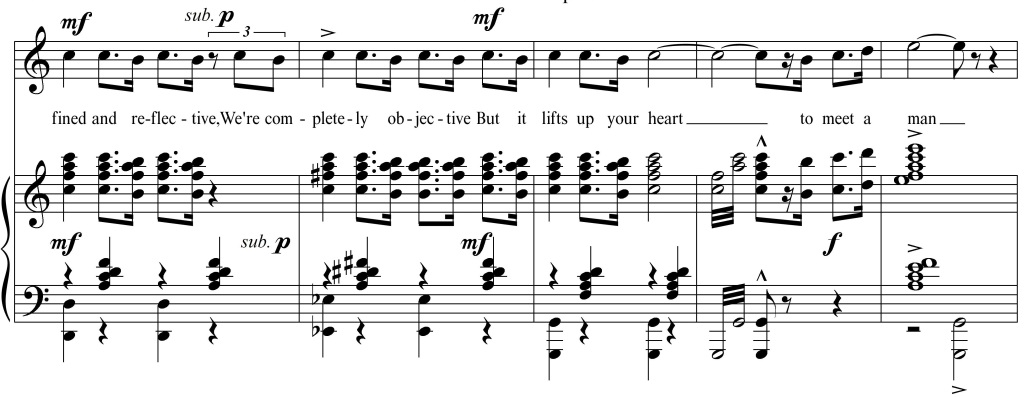

Try and figure it out yourself. Left hand pattern remains unchanged, in a 3 eighth note pattern. But the right hand is being constantly reconfigured. Measure 46 on isn’t too terribly hard, relative to the earlier work you did. I cut the harpsichord part in measure 68 and 69, because it threatens to drown out an important line. In the new score, the vocal parts are not properly identified from 68-71. Here is the passage as it appears in the original score:

The last passage, at 71 is too long for the dialogue, I think. If you watch the original production, you’ll see that the lines are delivered very slowly and deliberately. The sequence is very mannered, an approach which may or may not work for your production. It is quite difficult to get this passage under the dialogue, just as it was at the end of No Life.

- Cues in the Park

This number is three cues which are found elsewhere in the show. Easy.

- The Day Off (Parts I-VII)

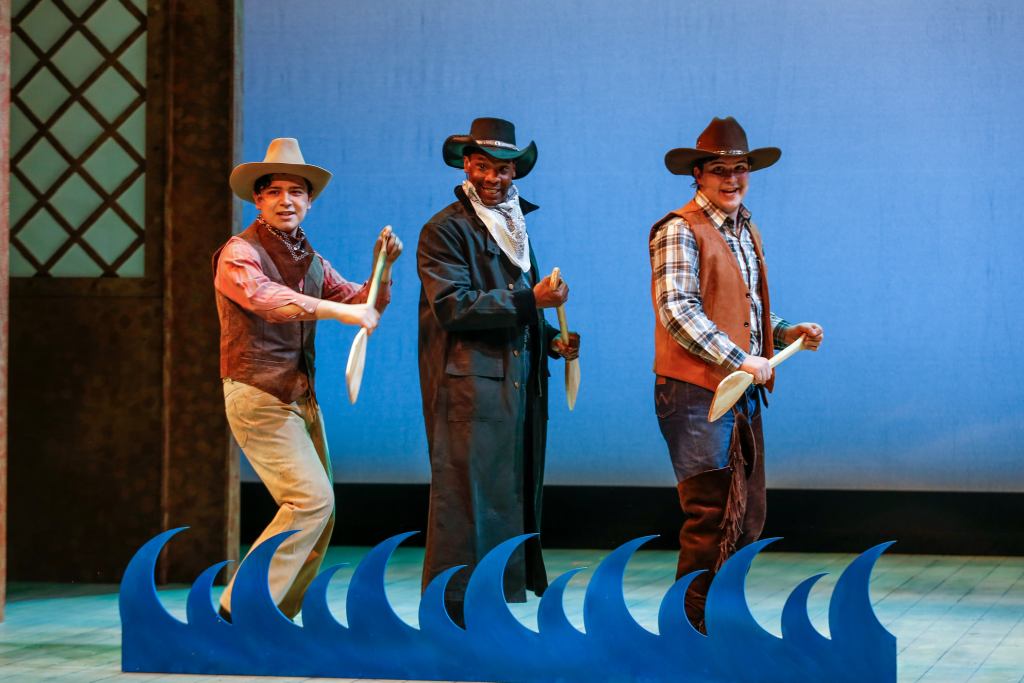

Along with Color and Light, this is one of the most distinctive, conceptually daring and expressive parts of the musical, and a showpiece for the actor playing George.

We have another example here of musical spaces. Spot’s initial music is punctuated by a dissonant, rather low chord reminiscent of the Boatman.

In Spot’s second portion, Sondheim introduces a rhythmic motive that will ground the rest of the extended number.

There’s a chord in this motive that seems very much like a point of stasis, and sometimes Sondheim will linger on it. Banfield identifies this chord as a point of stasis, calling it a ‘freeze frame’ harmony. This chord gives a feeling of ‘lift’, which is mirrored by a reappearance in Putting it Together.

Sondheim has given us grooves like this since at least The Little Things You Do Together from Company, but this instance seems very situated to function as a resting spot, a place for a snapshot.

A third groove emerges to close Spot’s section:

When Fifi comes in, she is accompanied by two percussive and dissonant chords in a higher register.

When the two dogs alternate, we see Fifi’s percussive chords (now mere 2nds) sitting atop Spot’s third groove, like so:

Despite the boatman’s conviction that Spot doesn’t expect anything of him, Spot turns out here to have a few negative opinions after all about the Boatman. And Fifi is also very judgmental about her companion.

Ultimately, though, I don’t think we can take this episode as reflecting any reality for the dogs themselves. These are George’s projections; he is play-acting the animals to get into their heads. We can tell this partly because the dog music George has constructed continues into George’s subsequent observations about everyone else. A transformation of George’s fanfare creative motive also appears regularly, which we may take as a musical indication that he is in his creative mode.

The Nurse and several of the subsequent subjects George encounters here SHARE simultaneous vocal lines with him. But they seem to follow these moments of agreement with their own distinct opinions,. apart from him. These shared lines include:

“One day is much like any other, listening to her snap and drone”

“Second bottle, Ah, she looks for me”

“You and me, pal. We’re the loonies. Did you know that? Bet you didn’t know that.”

“Mademoiselles, I and my friend, we are but soldiers!”

We also get the first appearance of the Celeste’s motive

It’s telling that we first get this jittery musical idea as we’re talking about fishing, an evidently unintended prostitution reference, if the literature is to be believed.

A purely coincidental connection is also hiding beneath the surface. If you slow the motive down and swing the rhythm, you’ll see that this motive is also a cousin to:

The melody that holds the larger sections together is inflected in so many different ways that we might lose track of their derivation from the same musical contour. Sing these to yourself and you’ll hear the continuity.

Frieda and Franz open up another angle on the outsider’s view of the artist: The wastefulness and privilege of the artist. For Jules and Yvonne, George’s choice of subject in painting the lower classes is in poor taste. But Fritz, even though he affectedly poses for George from his very first entrance, is perhaps too common to paint. Fritz dismisses him. Art isn’t ‘real work.’

The accompaniment pattern in 12F ingeniously retools the original gossip theme to fit above the established Samba pattern.

In measures 24 and 25, there’s a lyric discrepancy. In every production and in the original score, George sings, “Would you like some more grass?”, not “please, a little more grass.”

The passage in part one between 31 and 41 is very difficult to time to the meter. Mandy doesn’t follow the meter in the original cast, and neither do any of the subsequent recordings. We don’t particularly want to be tied up in counting these odd spacings when the actor needs to feel really freewheeling. This is not really a problem, except as you have to conduct it. Go over the vocal cues with the percussion, strings, harp, and horn, write some key words from the vocal into the parts, and cue the moments individually until you drop into tempo at measure 42.

The button at measure 121 was Michael Bennet’s idea. Having seen Patinkin make such a strong impression, it seemed wrong to deny him applause. But the button falls (to my ear anyway) in a nonsensical place; at the end of a section, to be sure, but without a closing phrase that feels like an ending.

In section 12B, in measure 37, the score is missing a new time signature. (¾, obviously)

The shifting right hand passage in 12F at measure 23 is annoying when you first encounter it, but it sure is fun when you get it under your fingers.

- Everybody Loves Louis

Another iconic song where much is done with rather simple musical means. George has spent quite some time conjuring the world of the park, to the point where we may even have begun to question whether we are in fact seeing reality or George’s editorialized version. Bursting suddenly into this world is a perspective that truly challenges George and calls him to account.

As we have seen, Sondheim thinks most clearly and speaks most effectively when he organizes thoughts into some kind of binary. This particular binary is stark and full of wordplay, made more effective by the fact that Dot almost doesn’t speak of George; the repudiation is by implication. As the number goes on, the comparisons are more and more personal and potentially hurtful.

| Louis | George (by implication) |

| Everybody loves him | Nobody likes him |

| Simple and kind | Complicated and cruel |

| Loveable | Difficult to love |

| Really an artist | A false artist |

| Not the smartest, but popular | Too smart, unpopular |

| Bakes from the heart | Too cerebral |

| Makes ‘bread’ | Doesn’t sell his work |

| Kneads her like dough | Is less attentive in bed |

| Pleasant, Fair | Unpleasant, Unfair |

| Present, Generous | Distant, Stingy |

| There | Gone |

| Easy to follow thoughts | Impossible to understand |

| Art not hard to swallow | Art difficult to digest |

| Makes a connection | Disconnected |

The crux of the song is of course her moment of vulnerability, set to the gently alternating chords Sondheim keeps returning to for these critical junctures:

We lose things,

and then we choose things

And there are Louis’s

And there are Georges

Well, Louis’s

And George

But George has George,

And I need someone

Louis.

To a certain extent, at least, Dot hasn’t really moved on yet. There may be many people like Louis. But if the one-of-a-kind George is unreachable, Louis will have to do. When we see this dynamic at work, Dot’s description of Louis develops a new dimension. She is not merely trying to make George feel bad. She’s trying to depict Louis in a way that elevates his art to a level where he bears comparison. Again we find a character framing reality to suit their own narrative. George is not the only artist.

(I was confused by the pluralization of Louis as Louis’s, and discovered to my dismay that this is in fact the correct way to pluralize singular words that end with a silent ‘s’. Try pluralizing ‘chassis’ and you’ll see the problem.)

There are passages throughout the score where no performer sings the notes on the page. The ‘Louis it is!” at the end is one of them. Try it once and see how alien it sounds!

The original piano vocal score and probably every other iteration you have played of this song contains the jaunty woodwind passage in the right hand. It’s hard to play this lick from the new licensed piano vocal score, but the polka piano part you’ll play in the show is easier to play ultimately, and much easier to establish tempo from, which is truly the most important aspect.

Measure 38 is a real conundrum. The three dots after ‘but…’ are impossible to convey to the audience if you plow directly into the next measure. Here are how the various cast recordings have solved this problem.

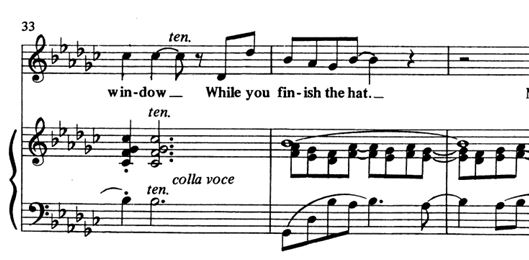

Annaleigh Ashford sings the rhythm that’s on the page, and we lose the feeling of the ellipsis entirely. This graphic with the tenuto marking is from the original score. In the new parts, that chord is marked staccato.

Bernadette adds a measure, singing something like this on the original cast recording and on the video:

Jenna Russell also adds a measure, but the piano retains the staccato chord, like this:

You will have to choose an approach and convey it to the orchestra. There isn’t any solution that honors both the music and the text in the score.

Measure 107 is a passages, now in 4, which here in particular needs to be in the correct tempo, because at 113, we find ourselves with the two musical ideas superimposed. You’ll want to think of 107 in the tempo of the Everybody Loves Louis chorus. I don’t think the fermata at the end works. You do what you like.

- The One On The Left

This was originally a much longer number. Sondheim explains it in Look, I Made a Hat. The last line of the original number is one that any other writer would have killed to keep in the show. You can hear the number as a bonus track in the 2006 recording. But the characterization in the shortened version is so strong that we don’t really need a much longer number to establish who they are.

The fact that the other soldier is a cardboard cutout is a wonderful and theatrical device, but it also justifies and draws connections to the George cutouts in act II. When we see them in Putting it Together, they haven’t appeared out of nowhere.

The fanfare melody of the soldier is one in a long line of fanfares going all the way back to Marcus Lycus in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum and continuing through at least 4 or 5 other scores. Sondheim uses this kind of figure to indicate silly, hypermasculine men. This particular version also owes a little to Stravinsky’s L’Histore du Soldat.

Work with the Soldier in 83 and 84 to really count the full measures, or the cue coming out of 84 will be tough with the orchestra.

Budget a little time to talk through measures 85-87 with the pit; the entrances in the parts are not particularly intuitive.

The bass part at the end of the number is just wrong. I’m attaching a correction here. It’s an ingenious little minimalist phasing: The right hand is in 4, the left essentially in 5. As it is in the licensed parts, that distinction goes away.

- Finishing the Hat

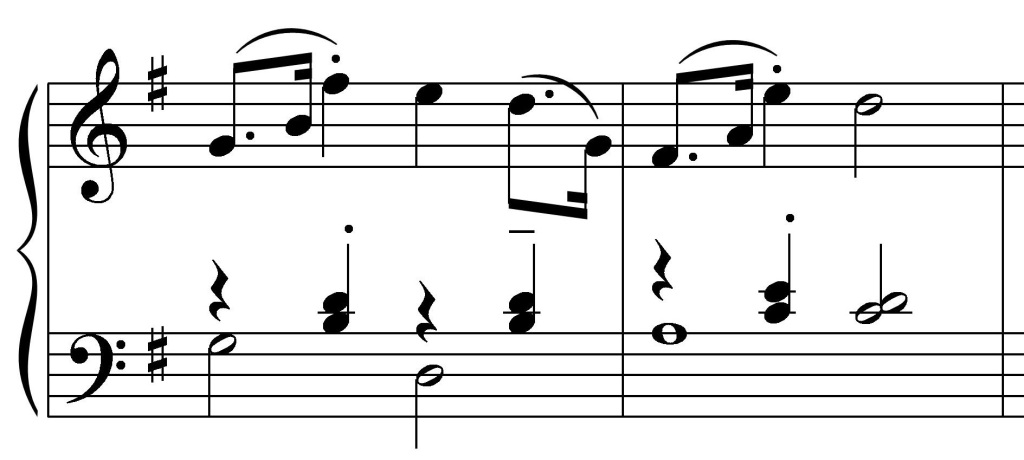

It took me far too long to realize that the order of the phrases at the beginning of Finishing the Hat are the reverse of the order they appear in The Day Off, even reversing ‘pastry’ and ‘chicken’ from their original order. Again these points of suspended time in the groove from The Day Off serve to underscore the quasi-reality of George’s recollections.

In a show full of superlatives, I have to trot out another. This number has meant so much to so many people. It is in a way the photonegative of Being Alive, another Sondheim ballad that has resonated with many people’s life experiences. Being Alive is about someone realizing that embracing the messiness of other people is the first step to finding authentic relationships. George, by contrast, is a person who is far more lost, because the true animating force of his life is the window to his imagined world. The imagined world will always supersede the real world of actual people.

This is the second appearance of the motive which will find its ultimate fruition in We Do Not Belong Together. Here it accompanies the revelation that George has had a number of women, and each of them was unable to deal with his temperament. She was supposed to be different, though, and when he gets to the line;

“But if anybody could…”

We hear the “But most of all, I love your painting” underscore, which becomes the basis of the accompaniment for the remainder of the song. The pattern here is not the same as it has been elsewhere in the show. Since I came to this number first, I thought this pattern was as it appears everywhere in the show, and I had to relearn it.

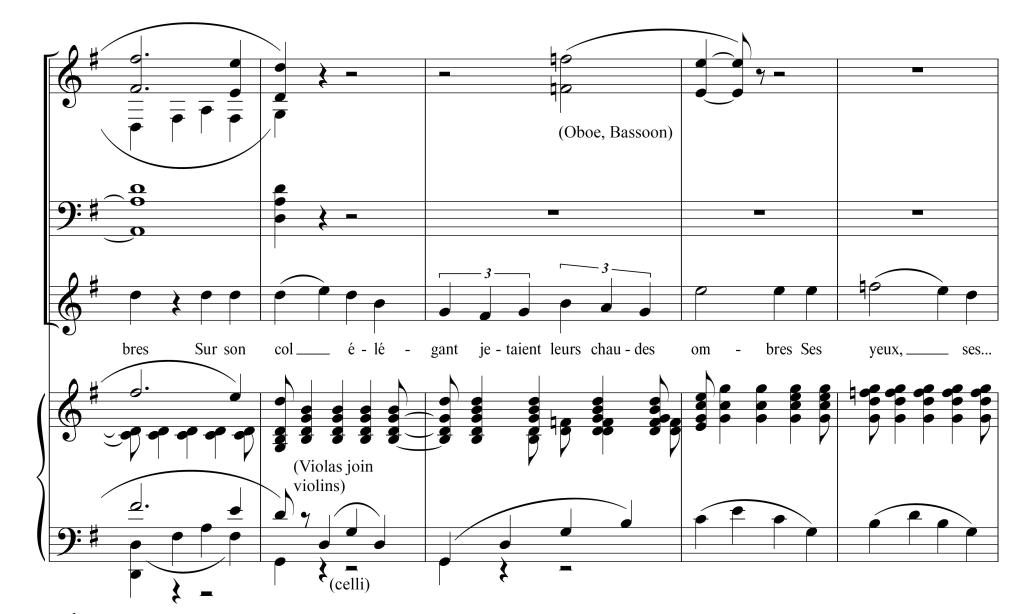

Here’s the way the figure appears in Everybody Loves Louis:

And here’s how it appears in Finishing the Hat :

They are, quite clearly, the same accompaniment pattern. But they are also fundamentally different. It doesn’t take much thought to find a dramatic significance to the musical detail.

Again, there is a kind of delineation of musical space, here actually on the word ‘window’, which stops the rolling accompaniment pattern in its tracks twice before the first major climax.

This climax, “and how you’re always turning back too late” is an extremely clear distinction, musically, between the two warring states of mind George is describing.

In Sondheim’s classic manner, the song then descends back into repeating patterns in both music and lyric, until George’s music eventually opens into a kind of a clearing to make the window metaphor explicit. This is followed by a repeat of the earlier delineation of musical space.

On the way into George’s final alienating observations, Sondheim uses the complete vocabulary he has established in quick succession:

Throughout this passage we get further into the nub of the issue with one of Sondheim’s central insights, one we find throughout his musicals, but particularly reminiscent of Buddy’s Blues from Follies. George actually wants to be in a relationship with a fully formed person, but that sort of person wouldn’t deal with the distant person that he is. This insight is what allows us to empathize with him; he recognizes his own unsuitability to any woman with self respect.

From this final desperation, George again descends into repeated phrases, the solace of the work. We can see that he has no intention of solving this problem. The hat doesn’t complain.

The original score has “I give all I can give” in measure 80. No singer actually sings that. Every recording, and the new score has “Well, I give what I give.”

At the end there’s an odd discrepancy. The Jake Gyllenhaal and Daniel Evans versions are performed exactly as the licensed vocal score now lays out the ending. But in the original production and vocal score, there was one more measure. The current score indicates two measures, but it really only cuts one as far as I can tell. Reinstating that measure would be fairly easy if one were so inclined. I’m not sure what is gained by cutting it.

- Bustle

This is one of the two chaotic sections which are very dependent on the staging. It isn’t clear from the score that the orchestra goes out of sync with itself as it accelerates, to a kind of cacophony, which is cut off abruptly at the bustle reveal. This section is aleatoric, a premonition of the Chaos to appear 7 cues later. One of the major questions in Sunday involves whether what we’re seeing is reality or George’s editorializing eye. At this moment, George is not in control, and the world is unorganized, formless. The one to stop this chaos though is Dot, as she reveals her pregnancy, again using a costume creatively to drive the action.

- Scene Change to Quartet (originally entitled Scene Change to Studio)

I found this scene change surprisingly difficult, because the ending isn’t really very easy to memorize, so I had to read the music. But the cue to end was on a lighting change, so I had to keep my eye out for the change. I ended up memorizing the last measure. The original score had another repeat, of measures 9 and 10. If you reinstate that repeat, you may have an easier time of it.

In the extraordinary scene that follows, we see a terribly revealing moment. George addresses the painting intimately.

“He does not like you. He does not understand or appreciate you. He can only see you as everyone else does. Afraid to take you apart and put you together again for himself. But we will not let anyone deter us, will we?”

He has forgotten that Dot is even in the other room.

- We Do Not Belong Together

This is the emotional climax of Act I, and the moment that I think most necessitates Act II. Sondheim had been using leitmotiv for a long time, especially in Sweeney Todd, but here the deployment of accompaniment patterns is simple and calculated, to devastating effect.

We begin with the ruminating two-chord pattern, which has been reserved so far to accompanying lyrics involving George’s vision and the effects of that vision on the self worth of the people around him.

“Your Eyes, George…”

“If my legs were longer”

“If I was a folly girl…”

“And he burns you with his eyes”

“If the head was smaller…”

“Hello, George, where did you go, George?”

“The bread, George…”

“We lose things, and then we choose things”

“Yes, she looks for me. Good.”

When Dot accuses him of caring about things and not people, the music shifts to the third and final iteration of this accompaniment pattern:

Dot is more pointed and unguarded here than at any other point: George is using her. He only cares for himself. We find ourselves in another whirlwind of repetition, which Dot releases in a brand new section we have never heard before:

“You could tell me not to go.”

George doesn’t join here in this new material, but retrogresses into the earlier musical material. “You know I cannot give you words”

All this has been leading up to a brand new idea, the transformation of George’s opening fanfare to a turbulent, roiling accompaniment in D minor.

Compare the right hand of that figure to the second fanfare from the opening of the musical (both hands in treble clef in E flat major):

If the opening image of the show was George’s mastery of his world, this is the beginning of the disintegration of that world which will shortly lead to Chaos, a kind of ‘darkness on the face of the deep’

George is helpless. He can’t see it from her perspective. She knew what she was getting into. This music will take on new meaning in Act II, but here, George’s attempt to command the narrative fails because Dot again reasserts her argument with another new motive that he does not participate in. The new motive is based on the first iteration of the opening fanfare.

Sondheim did all this very deliberately, of course.

“It seemed effective to use rhythm to reflect putting dots on the canvas, to show his distraction as well as his concentration. But that, of course, becomes motivic, that rhythmic idea. There are two basic rhythms, actually: There’s the arpeggiated rolling rhythm that is set up right in the opening arpeggios and eventually becomes Finishing the Hat and the kind of rolling vamp in Sunday in the Park with George, then there’s the painter’s theme, which is sharp and staccato and jabbed. That, combined with the rolling vamp, becomes Move On.

The line, “I am unfinished with or without you” is troubling, but also brutally honest. Leaving an unhealthy relationship is leaving a diminishment, while also being itself a diminishment, because you leave part of your identity with the other person.

I think most people respond viscerally to the lines,

“No one is you, George, There we agree,

But others will do, George.

No one is you and no one can be,

But no one is me, George,

No one is me.”

She is developing her earlier thought:

“There are Louis’s and there are Georges,

Well, Louis’s and George.

But George has George, and I need someone”

But now she’s arrived at the fact that she is herself a singularity worthy of respect.

By the time she begins these lines, George’s fanfare motive has disappeared from the accompaniment.

The creation fanfare comes back as she changes tactics to affirm his mission:

“You have a mission, a mission to see.”

Sondheim denies Dot a button to applaud, and as she leaves, the fanfare motive disintegrates as George is left onstage. We transition back to the ruminative motive, and George is alone with his mother.

I’m not sure it’s possible for a production to truly capture everything that’s bubbling up in this number, but in terms of the structure of the musical, George has lost control of his world, and he has no tools to reclaim it. Against this backdrop, Sondheim is poised to explore the ephemerality of all art.

There’s an awkward violin voicing in measure 50 and 51. (the 5th at the top of the first violin) The voicing does appear in Cecil Forsyth’s orchestration textbook, which is where I suspect Starobin got it. Let your players do what seems best to them, but I can think of a couple of workable solutions that preserve the idea well.

- Beautiful

I usually skipped this when I was listening to the CD as a kid, but when I was working on the show, I came to find it one of my favorite moments. It’s critical to the exploration of the artistic process, and even though it slows the action of Act I, it can ONLY be here, where it will say the most to us.

The Old Lady, as the script calls her, had earlier been reluctant to sit for George, but now she consents to be depicted, and the script describes her as having ‘a kind of loving attitude, soft and dreamlike’. She begins by recalling a past that George disputes. We sense that George may be factually correct, and that his mother has edited the past to make the memories more pleasant. George’s mother lives in the past. As she looks, she sees a world counter to the imaginary past of her memory. Towers, noisy children, they’re all a kind of aberration. Like Jules, she resists change. But where Jules resisted artistic change, the Old Lady resists reality changing.

We discover telling details about George’s distant and unfaithful father. But as tantalizing as those details are, I think another dynamic is more fascinating still. The melancholy disappointment of George’s mother opens up a place where George can speak a truth that is key to the entire piece. The people, the relationships, the joys of life, the landscape itself are constantly in a state of becoming something else. This is a beauty in itself. What gives the changing thing any meaning at all is what it comes to mean for the person who sees it, who remembers it. This is a lovely parallel to the method George is trying to pioneer. The eye of the viewer literally constructs the colors of the painting.

Any depiction of this changing world will always be a revision, just as George’s mother is continually revising the past.

“I’ll draw us now before we fade, Mother.

You watch, while I revise the world”, George suggests

“Quick, draw it all, Georgie… You make it beautiful.”

“Look! Look!”, George says.

This is perhaps the only true connection George actually makes with another living person in the first act. But as the number concludes, George’s mother slips back into nostalgia. “How I long for the old view”.

Following this song, the promenade of characters slips out of order. Fights start, each relationship is in danger of splintering. This number with his mother begins the last big shift of the act, as George names and inhabits his role of idealizing and permanizing the world.

I recommend you copy the Piano Synth part and give it to your Keys 2 player. That will free you to conduct, Keyboard 2 doesn’t have much in it, the Piano Conductor score is missing some important Keyboard 1 music, and in all likelihood, your singer and your players will appreciate seeing your hands getting through the tempo changes and ritardandi. The harp part has one rather awkward pedal change. To manage that, your harpist may want to do the number slower than your singer would. With practice, the pedal change becomes manageable. I wouldn’t bring it up with the harpist, but I would be aware of the difficulty.

Measure 14 in the licensed materials has a lyric error: It should read:

“I see Towers where there were trees”

Measure 59 in the new score is missing a left hand part; it ought to read as measure 55 would.

- Soldier Cue #1

This is tricky to cue because the cue line is in the middle of a lot of overspeaking dialogue. Ears open!

- Jules and Frieda

This is in keyboard 2, but you may as well play it yourself, if you’re conducting from the first book. It’s disorienting music, and it keeps the bizarre seduction scene from reading fully as comedy, which I think is intentional.

- Soldier Cues #2 and #3

Again, a very simple cue

- Chaos

This is the second and climactic chaotic section, cued clearly to the action. (George frames the scene) Each production is going to cue this slightly differently.

Dot’s final break with George has somehow broken a delicate equilibrium. Each character is involved in an irreversible disruption. All relationships are being broken.

If we’ve built up the right kind of momentum in the act, we will experience the beginning of the next number as a jolt, as the Old Lady tells George: “Remember!”

- Sunday-Finale Act I

Sondheim explicitly tells us that the chorus here are figments of George’s imagination. I’ll let you read in Look, I Made a Hat about the fragmentary expression, what made Sondheim cry in this number, and more. I won’t deprive you of the pleasure of discovering those things yourself.

The first act finale draws together all the threads of exploration we have explored over the previous hour, as George arranges out of the chaos an idealization of these people and this place. Dot is somehow with Jules. No one faces the painter. Louise loses her glasses. Dot gets a monkey.

Near the top of the show, George had casually said that he was drawing the monkeys, not their cage. This depiction is an idealization of the monkeys (these characters). It doesn’t depict the cages in which they find themselves, socioeconomic, interpersonal, and otherwise.

I think one of the things that makes this song so meaningful for people is the juxtaposition of the painting’s perfect order with our memory of George’s loneliness and the entire cast’s alienation from each other. In George’s idealized world, no one looks at him or one another. Some have written that Sunday is a perpetuation of romantic stereotypes about the tortured artist. I think this reading misses a lot of nuance. Everyone in the piece is disconnected. Everyone in the piece is reframing the reality around them. George is just the one who creates an artifact; the painting. The piece doesn’t particularly ask us to pity George (who is generally rather unpleasant) or rail at an unfair world (George gets a pretty fair shake). It asks much more troubling questions about how each of us sees the people around us. It further asks us why we are so moved by these particular idealizations.

The piece doesn’t answer these questions.

Banfield notes the striking harmony before ‘of the grass’, where a c sharp in the right hand rubs against a strong C natural immediately thereafter in the bass, implying secondary dominant and the subdominant at basically the same time. (we are in G here)

There are a variety of convincing tempi for this number, but you may have things flying in and out that require a particular timing. Keep that in mind as you teach it.

If you listen to the original cast, you will discover that the cutoffs indicated in the score are not observed; Nearly all the choral moments are cut off on the downbeat of the next measure. I did not do this in my production, but it is a change I recommend, since the cast is by necessity looking offstage right, not at you, and the cutoffs as indicated in the score are not intuitive.

At the end of the song, the violins are conscripted into the percussion section. Have a look and figure out what you want to do there.

The licensed materials have an error at the end of measure 58. That last ‘bum’ shouldn’t be there.

- It’s Hot Up Here

The opening of Act II is the counterpart to Dot’s opening number, the opening section a tritone away in key. (as far as we can go) We used to be in Dot’s uncomfortable world, literally chafing against the confinement. Now ALL the characters must conform eternally to George’s vision, and they don’t care for it.

This number is the true close of the story of act II, but it could really only go here, at the top of a very different act.

The original cast recording was organized to be like a cantata, a freestanding musical journey. That has sort of blunted the original intention of this moment. We are meant to be uncomfortable. When the curtain comes up after the act break, take some time. Let the audience wonder if something has gone wrong.

The stage direction reads:

(Lights slowly fade up. Long pause. Audience should feel the tension as they wait for something to happen. Finally, music begins)

When you begin, leave a lot of space in the first fermata. The number lands better coming from this place of discomfort.

While the accompaniment pattern derives from Dot’s Act I opener, the melodic material is new. The chorus that follows is totally new, although the melody is an elaboration of ‘It’s hot up here’. The accompaniment is a rough draft for the title number of Sondheim’s next show: Into The Woods.

The centerpiece of the section keeps it from being merely a comedy sketch:

“Hello, George, I do not wish to be remembered like this, George”

The accompaniment, melodic contour, and harmonization have changed, but this is clearly a continuation of the act I thematic idea, which is always about their relationship, and how he sees her.

As impressive as Dot’s long phrase is at the end of her first number, the group version at the end of “It’s Hot Up Here” is more so. Budget a lot of rehearsal time to solidify the passages from 36-43 and from 81-88. Initially the challenge is to make the entrances one after another. But this is live theatre, and the true goal here is to know where your part goes EVEN IF ANOTHER ACTOR MISSES THEIR CUE.

In the tutti sections, as after measure 15, it’s about crisp diction. Make some decisions about where those cutoffs go and drill them from the very beginning. (in particular the ‘t’ of ‘what’ in measure 22)

The nurse has a line “I put on rouge today too” somewhere around measure 85 in every version of the script, but in no versions of the score. I can’t hear it in any of the cast recordings. If anyone knows where that’s supposed to go in the melee, please put it in the comments.

There’s some rather ineffective scoring in the passage beginning at 108. The horn, (stopped) and cello have an offbeat pattern that plays against the bass and the left hand of the piano. Those instruments don’t really blend, and can’t properly establish the musical idea, so it sounds like they’re playing the piano left hand part incorrectly. I don’t have a solution, but to my ear, it doesn’t really work.

It’s unclear how the (s)he’s in the lyric at 106 is supposed to work. I read it as each character being annoyed at their antagonist, and the characters choose the correct pronoun for the person who annoys them.

Carefully drill the timing at the end, so that the ‘t’ at the end of the final ‘hot’ is exactly in the right place. They will all be looking offstage right, so you will not be able to cue them.

- Eulogies

The printed script I have from 1991 and the version included in Lapine’s new book include a long monologue for George after It’s Hot In Here. It depicts from George’s perspective childhood memories and then eventually what seems to be the beginning of his final illness. The monologue is not in the video of the original broadway production. I don’t think this monologue should be reinstated, but it is interesting that George says:

“A mission to see, to record impressions. Seeing… recording… seeing the record, then feeling the experience. Connect the dots, George.”

Sondheim and Lapine were, I think, starting to lay the groundwork here for the key questions of act 2, and to draw them back into act I in a way, to remind us of Dot’s need for connection, something Louis made and Act I George could not. The idea of trying to make connections permeates all Sondheim’s work and in particular looks forward to Assassins. “Connect! Connect! Connect!” (Everybody’s Got the Right to be Happy)

The music of Sunday is kind of a grab bag of 20th century techniques:

French Impressionism in No Life and Beautiful

Aleatoric music in Chaos

Stravinsky in The One On The Left and in the 3 dissonant notes before the vamp begins in Sunday

Minimalism in Color and Light, Gossip Sequence, Putting it Together, and elsewhere

Electronic Music in the Chromolume

Jazz in the Cocktail sections of Putting it Together

The notes of the first section underscoring the monologues are a 12 tone row, although Sondheim doesn’t develop them. After the initial statement he repeats on a synththem getting faster and faster.

The nerd in me wishes there were some significance for each of the 12 pitches to the 12 people exiting the stage, but there isn’t any clear correlation.

The row repeats in measure 13. I made that loop as an audio cue, which is, I think, the only way to do it effectively. If you can play that 12 tone loop at speed getting faster and faster, you’re a better musician than I am.

- Chromolume #7 (Part I)

This part of the show disappoints some viewers, (see my earlier post) but I think it was shrewd of Sondheim and Lapine to make George’s art non-representational. It takes off the table the first act’s questions about seeing and being seen, whether the artist should have license to edit the world. This leaves the field open to be able to talk about the complicated world of selling the art you make.

I was so carefully looking for patterns in our production, I suddenly became convinced that Naomi Eisen was somehow an anagram. Some grad students were concerned for my mental health… (thanks, Sloan and Alison!)

I started by playing this on my keyboard with a pad, but I found the drop with the pitch wheel didn’t go down far enough to sell the instrument breaking down, so I built an audio cue with a lot of crackling nonsense sounds at the end in addition to the drop. I found this much more effective.

- Chromolume #7 (Part II)

I built this in an audio program using free synth plugins that imitated the analog synths used in Stranger Things. For the first 21 measures, You’ll see that the patterns essentially layer on each other. I made all the layers, each in their own tracks, and then I exported the stems so they were on the click together. The sound designer then pulled those stems into Qlab and set up the cues so each click would unmute a new stem.

The process begins again at measure 22, but without cueing, so you can just time it out the way your production needs it. My sound designer wanted to manipulate the individual synth loops in the 3D soundscape, so I gave stems for that as well, which he sent to various speakers. It was a neat effect.

All this was originally performed by pit players activating synth loops from backstage. Pre-recording a track is much less stressful, I would imagine, and has the same effect.

My production really wanted a button at the end as well, so I built a synthy conclusion.

- Putting it together (Parts 1-17)

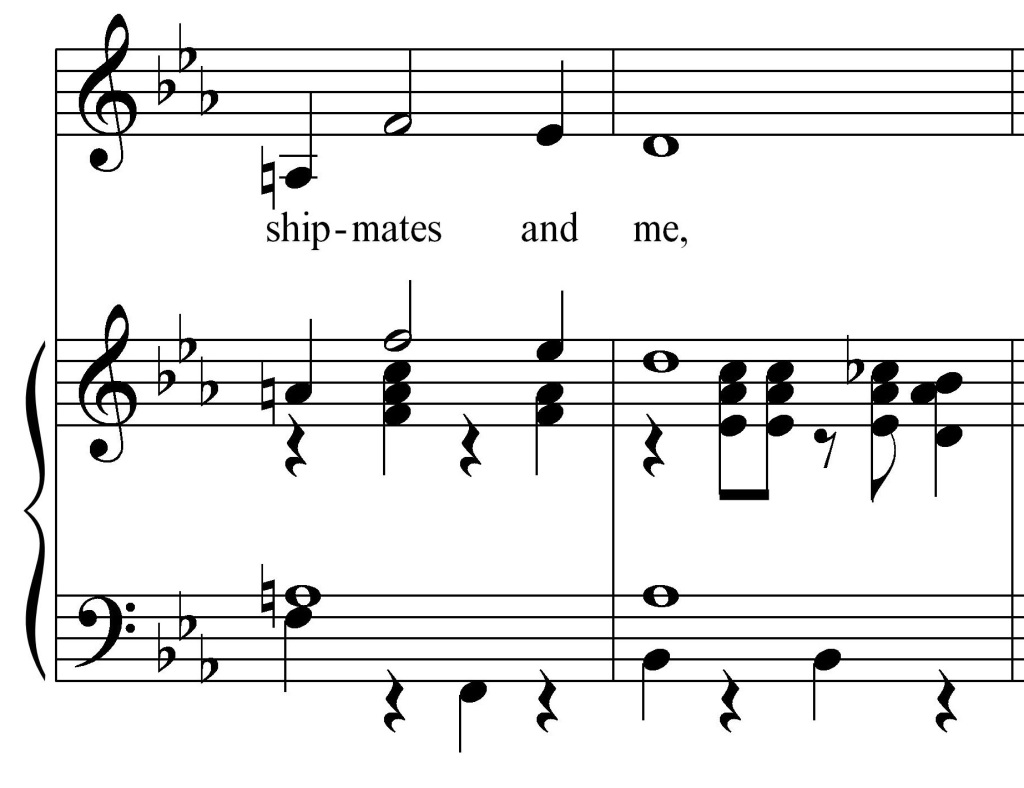

For an extensive analysis of this number, please see How Sondheim Found His Sound by Steve Swayne. Sondheim had been chasing a number like this for a long time. Its antecedents can be traced in Yatata Yatata from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Allegro (for which a very young Sondheim had been a gopher)

Most recently, Sondheim had written a very extended and somewhat similar party scene called The Blob in Merrily We Roll Along. But the previous attempts pale in comparison to this number, which accomplishes so much and is so satisfying.

The material not associated with George echoes Jules and Yvonne’s No Life and the Celestes in the Gossip Sequence. The responses to the new art will always be perplexity masked by boredom. The marked difference between the gossips of Act I and these gossips are that none of the Act II gossips are concerned with anyone’s personal lives. Instead they argue in vague terms about the art itself. Alex has taken the place of Jules as a jealous artistic antagonist, and there is a running theme that art is inscrutable and that fashions change all the time. In that respect, the art world depicted here is quite different.

Jules in Act I:

“(getting angry) Always changing! Why keep changing?”

Later, George offers this counter to Jules:

“Why should I paint like you or anybody else? I am trying to get through to something new. Something that is my own.”

In Act II:

Greenberg:

“It’s not enough telling good from rotten

when something new pops up every day.

It’s only new though for now, but yesterday’s forgotten”

Redman:

“And tomorrow is already passé”

Greenberg:

“There’s no surprise”

It’s a curious inversion of the dynamic of Act I. The Act I world at large was constantly being revised, but the art world resisted change. Here the art is constantly changing, but the outside world seems oddly familiar. Again we find ourselves discussing the ephemeral and the malleable. But Act II George is no longer lost in the wonder of the creation; he is too busy on the promotional end of the art. George’s entrance is heralded by the same fanfare as in act I, but he is not the same George.

Mandy didn’t realize it until many years later, but George’s melodic contour in Putting it Together mirrors his melody in Finishing the Hat. This underscores the fundamental problem of Act II George: His energy isn’t in creation, but promotion, which is unsustainable. It’s hard not to conclude that this insight is related to Sondheim’s disillusion with commercial theater after the failure of Merrily.

The inclusion of George’s multiple cutouts is a stroke of theatrical genius that is a parallel to Dot’s dress exit in act I, and just as central to the narrative. Dot’s stepping out of the dress allows us to see her as George is depicting her and also as she is in her own identity. George’s multiple versions of himself reveal that the locus of George’s creative energy isn’t the chromolume, but his public persona. He is the product, not the art.

This is by far the most difficult number of the show. As I was rehearsing it, I wondered if I was, in fact, capable of playing it! Slowly, solutions became possible, and I actually developed quite a facility in executing the patterns. Don’t despair, but do plan to practice!

The cocktail piano versions are in the same rather unimaginative lounge style we also find in Merrily We Roll Along, but don’t go too crazy embellishing or improving them, because they all sit under dialogue, and you don’t want to draw focus.

The end of Part 4 had a break in the original production. (see video) You’ll have to decide how to manage it.

The original production did not tie into measures 4, 6, 8, and 10 in part 6. Instead, measures 3, 5, 7, and 9 were just 3 staccato chords each.

Part 7 is much faster than the metronome marking. The original production plays the underscore around 90 beats per minute for the dotted half, and even at that clip, they almost don’t make it by the end of the dialogue. You will also notice that the part is simplified. It might be wise to write in chord symbols and find your own simplification on the fly.

29K is a fingering conundrum. I don’t think it makes sense to go into too much detail because each hand will be different. I will say that however you divide the pattern between the hands, you’ll probably need to adjust it at some point.

In part 13 (29 N) The 5/4 bar originally went with a camera flash. I think trying to establish that extra beat is a waste of time, especially since nothing happens in the bar musically. Think of it as a lift, and tell the players to do the same.

Measures 24 through 27 of 29 O were particularly awkward to play for me, although in looking at them, I can’t make out why. Measures 34-36 are hard for the singer to feel. Try and orient them to the Bass line as you rehearse it. I toyed with the idea of cutting a bar out, but the patterns are impossible to truncate; if you cut anything, the next passage doesn’t line up correctly.

The opening of 29P is hard to time against the dialogue. Learn to play it yourself, and cut the second keyboard (they don’t really add anything to the proceedings here)

Measures 57 and 68 of 29P is another place where it isn’t worth it to try to get the 5/4 accurate. Think of them as a little lift.

From 71 on is the most difficult part of the show. Sondheim reserves these all-cast cacophonies for very particular moments: God That’s Good comes to mind, A Weekend in The Country from A Little Night Music or the Interrogation in Anyone Can Whistle. The cast recordings naturally have George’s vocal in the forefront, so most people have never really heard the other lines well. They are VERY fast and come in at difficult spots. Your right hand can go on autopilot, but your left has a very specific offbeat pattern that is difficult to execute. If you have the time, get a nice loud metronome (through a sound system?) and teach the parts at a fraction of the speed. Once you have the parts roughed in, increase the speed by a few beats a minute each time until you get near the indicated tempo (half=116) You really can’t cue this from the piano as you play. They just have to know it. In truth, the most critical part of the ensemble singing is the downbeat of measure 93A “That is the state of the art” Teach your singers how to listen for George’s line OR the bass. Hearing the half note in measure 90 and then the subsequent 3 bars can really help land that tutti entrance. In measure 92, Harriet’s part goes quite high. I think that 2 measure phrase should really be down the octave.

- Children and Art

This is another number that is difficult to get excited about when you’re listening to the cast recording, and frankly in performance. According to the stage directions, three times in the piece the singer nearly falls asleep, and the lifts at the end of each measure are part of that sleepy disorientation. This means the vibe can be dangerously narcoleptic, a relief after the adrenaline of Putting it Together, but not exactly what you’re hoping for in the middle of a second act.

But when we see it as a bookend with Beautiful, not necessarily thematically, but functionally, Children and Art really starts to pull a lot of weight. Marie is beginning second act George’s journey from disconnection to healing. In order to get there, George has to ground himself in the heritage of act I George. Marie has to introduce her to his grandmother, because the way back is the way forward. Marie is not the kind of character to sermonize, though. That happens later. This lyric is oblique to the main thrust of the narrative, and diffuse compared to the dizzying specificity of the lyrics we’ve just heard.

I was bewildered by Sondheim’s frequent references to this as a Harold Arlen song. What could he mean by that? I think I finally cracked it while playing the run of the show. Arlen’s torch songs, like Come Rain or Come Shine, The Man That Got Away, or This Time The Dream’s on Me have a kind of slow burn repetition that suspends time in an odd way, that reminds one of slower songs in general, and this song in particular, as foreign as the style may be.

The last chord seems to be hard to voice because of the dynamic levels in the ranges of the instruments as they are laid out. Play around with it at the sitzprobe until it sounds balanced.

- After Children

The cue for this is “Connect George, connect.” It takes us into the final scene of the show, on the island as it is in 1984.

- Lesson #8

This was the last song added to the show. The original title was ‘primer’, which I like quite a lot. As the song stands now, we may lose a little of that connection. Dot was learning how to read, and now George needs to learn something too.

Sondheim’s writing here is again somewhat oblique, but that seems only to increase its effectiveness. Patinkin evidently even prefers this moment to Finishing the Hat, a number I would imagine is much easier to act. George doesn’t have any epiphanies here, it’s a moment of despair. As Sondheim describes it:

“He has no center. He has no vision. He’s not connecting. He’s feeling empty.”

The action accomplished here is the conjuring of Dot.

Only the 2006 recording has measures 7-12 as rhythmically notated. It’s one of the easier numbers in the show to play, so you and the actor can really find the trajectory and the phrase rhythm of the piece.